This far SW coast of Cornwall, from Land’s End around to Porthcurno, is a windswept rocky place which bears the brunt of the Atlantic storms as they crash against the towering granite cliffs. It is an area littered with shipwrecks and tales of smugglers and witchcraft. Gwennap Head lies at the very south west tip of Cornwall, a few miles south of Land’s End (although it is debatable where is the true lands end of the country!). South of us, over the horizon, lie France and Brittany. To the west, the Isles of Scilly (or, perhaps, peaks of the legendary lost land of Lyonesse!) are often visible and between the two, the vast Atlantic Ocean and the Americas.

From Gwennap Head there is a spectacularly panoramic view of the sea and, through the seasons, we witness every possible sea state, weather-mood and light condition. There is always something to be seen; passing sea birds, gannets diving for fish, men in cove boats fishing single-handed for mackerel or bass, near the Runnel Stone, larger boats heading out for a day’s work, trawlers setting off for several days at sea and yachts passing by on trips to places unknown

An idyllic location…but it has another darker side!

We watch over one of the most dangerous stretches of water in the UK. With Wolf Rock Lighthouse and the infamous Runnel Stone Reef close by, this treacherous coastline has seen many hundreds of wrecks near the station, and between us and the Scilly Isles. Their stories behind these are often strange and or tragic, rivalling the worst wrecks that have occurred around the world. Christine Gendall’s family fished out of Porthgwarra for at least three generations and they knew that area of cliffs, rocks, tides, and weather conditions, intimately. Over the years, various family members were involved in tragedies and rescues from the sea, which then dominated their lives. In this extract from her book, Porthgwarra (reproduced with kind permission of Churchtown Technology, St Buryan), Christine gives a personal insight into some of the many shipwrecks around Tol Pedn and the neighbouring village of Porthgwarra.

In this congested area, three Traffic Separation Schemes (TSS) exist to control the navigation of all vessels joining, transiting, crossing and leaving the schemes. There are three TSS’s off Scilly – to the east (between the Isles and Land’s End), to the south, and to the west. In the area between each TSS and the adjacent land there is also an inshore Traffic Zone, from which all traffic is prohibited. Traffic is relatively dense in the east TSS, but the tidal stream generally runs parallel to the coast, whereas the south and west TSS’s are more exposed to westerly swell, and the tidal stream generally run perpendicular to the Isles.Together with Cape Cornwall NCI, we are able to provide visual, radar and AIS coverage of this very busy zone. As well as the large commercial vessels, we identify and log the many fishing boats, pleasure craft, kayaks and dive boats in the waters around our station.

The west coast of Cornwall is sometimes called Granite Country and, indeed, just below the watchtower, appearing to be built from large cubical blocks, the granite Chair Ladder is considered to be the finest mass of stone in the county. This, and the surrounding cliffs are a magnet for climbers from all over the world particularly in the summer months – another thing for the NCI to keep an eye on! We watch out for these climbers and also the many walkers and bird watchers on the coastal path.The Lands End Cliff Rescue Team use the cliffs as a training centre.

Porthgwarra is a pretty little fishing cove, nearby to Gwennap Head. It’s name ( meaning The Higher Cove) is generally considered a corruption of the original 1302 name Porthgorwithou, literally translated as The Cove by Wooded Slopes. There are tunnels cut through the rock to give access to the beach. Some say these were used to help with ‘freetrade’ (i.e. smuggling) in olden days. The following paragraphs are taken from ‘Porthgwarra’ by Christine Gendall.

Cornwall has a historic reputation for smuggling. I find it hard to accept that fishermen and farmers would lure ships ashore by false use of lights. Though I do believe that they may have been involved in some illicit trading in spirits and tobacco. If there was a wreck, they did their utmost to help the crew get ashore….. but were then swift to assist in the salvage! I have spoken to Jean Hey (nee Rawlings) and David Williams, both of whom played as children at Porthgwarra. They remember playing in a smugglers’ cache, a hiding place on the cliff top, inland from Hella Point some distance behind the marker cones. In recent years they have independently searched to try and find the top entrance of this rock covered cave, but have been unsuccessful due to profusion of the undergrowth.

Sadly, the truth about these tunnels is a bit more prosaic! Around 1880, the tunnel was built by St Just miners, primarily, to improve beach access for the local farmers, who would collect and remove seaweed, for use as fertiliser on their potato crops. Apparently, the farmer’s horses, pulling the seaweed-laden carts, found the fairly steep tunnel floor slippery and a lot of effort was needed to persuade them to go up the tunnel! Actually, the main tunnel used to have two different openings, in a figure-of-8, until the intervening floor collapsed….which may or may not have happened during the Mount’s Bay earthquake of 1996….Yes, on the 14th November, at 09.30, we had our very own earthquake, centred on Mounts Bay and registering an earth-shattering (well, actually, more like jelly-wobbling!) 3.8 on the Richter Scale. As one local paper put it:

Windows rattled and loose plaster fell from houses and animals were alarmed, but there were no reports of injuries or serious damage to property. The most it did was to move pictures on walls and shake items around on tables and cabinets.

The Runnel Stone Until recently a moaning sound could often be heard over the area of Gwennap Head. This emanated from the buoy which marks the Runnel Stone (previously called Rundle), a hazardous rock pinnacle about a mile offshore between Hella Point and Gwennap Head. The buoy is now topped with a flashing light and a bell, which peals with the movement of the waves. The moaning came from a whistle set in a tube which sounded when there was swell running. This was recently removed from the buoy by Trinity House. Today the Runnel Stone draws divers from all over the globe who come to explore the many wrecks which have come to grief at this dangerous spot.

Near our station on the cliff top, and inline with the buoy, there are two cone-shaped markers. Despite local stories, these are not rockets or our last line of defence! In actual fact, they are Day Markers, warning vessels of the hazardous Runnel Stone. The cone to the seaward side is painted red and the inland one is black and white. When at sea, the black and white one should always be in sight….. but if it is completely obliterated by the red cone, a vessel would be on top of the Runnel Stone and, at serious risk! A plaque on the black and white marker cone reads “THIS BEACON WAS ERECTED BY THE CORPORATION OF TRINITY HOUSE OF DEPTFORD, IN STROUD 1821”

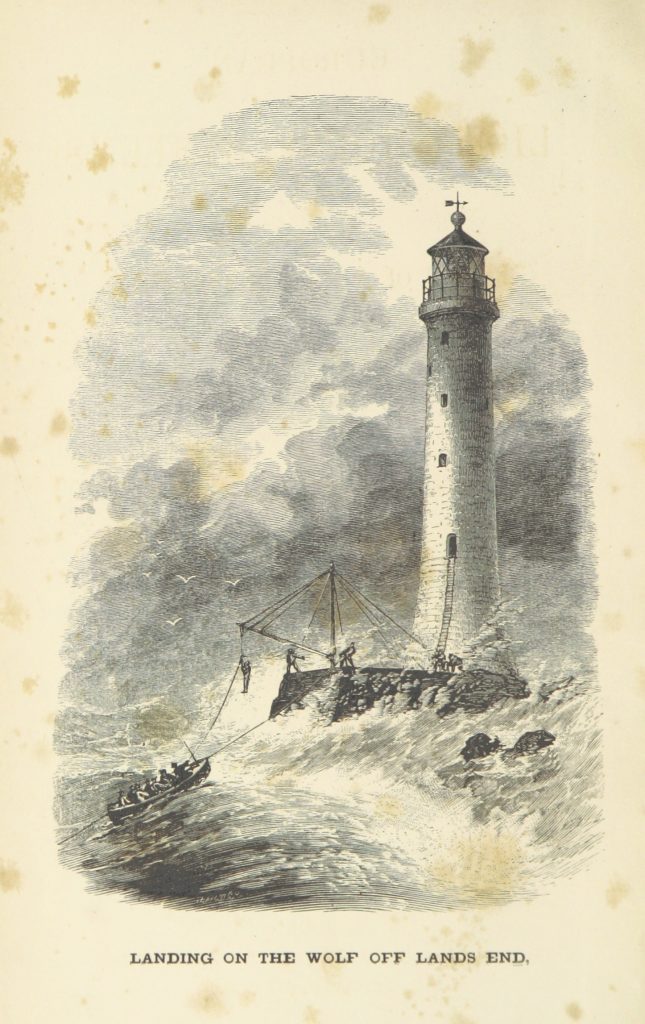

Wolf Rock 7.5 miles off Gwennap Head, this rock was (and still is) a constant danger to shipping, it’s name coming from the eerie howling sound, said to have emitted from a cleft in the rocky reef. Allegedly, when the wind blew from a certain direction a weird noise could be heard if you were close by! This led to the rock’s already ghostly reputation and local fishermen attempted to ‘silence’ Wolf Rock by filling the hole with stones. A number of attempts to put a beacon on the rock were made between 1795 and 1850, finally a lighthouse was built on it between 1862 and 1870. The rock is particularly dangerous, as there is deep water virtually all around it. Even in good weather, swells surge over the rock, so the construction was very difficult. The stone blocks were cut, shaped and fitted in Penzance. Just over 1000 tons of rock was needed for the base, and 3300 tons of granite used for the tower.

The first 39 feet of the tower is solid, thereafter, a 7ft 9″ wall starts, then tapers to 2ft 3″ by the time it reaches the top of the tower, some 116 feet above the rock. The final stone was put in place in July 1869, and the light first shone in January 1870. The oil-powered light was replaced by a generator-powered electric light in 1955. With a range of 23 miles, the signal is one white flash every 15 seconds, and there is a fog signal belting out every 30 seconds. Although originally manned (in 1912,the weather had been so bad that keepers were stuck on the Rock, without relief, for eleven weeks), it was automated in 1988 and is now unmanned.

Sevenstones Lightship is a lightvessel off the northern end of the Isles of Scilly, marking the notorious Seven Stones Reef.The reef has been a navigational hazard to shipping for centuries with seventy-one named wrecks to it’s ‘credit’, and an estimated two hundred shipwrecks overall (the most infamous being the oil tanker Torrey Canyon on 18 March 1967). The rocks are only exposed at half tide and, since it was not feasible to build a lighthouse there, a lightvessel was provided by Trinity House, instead. Until the late eighties, the vessels (there have been five) were manned and, as can be imagined, it was no easy duty, with illness, falls and even drownings being not uncommon. Having said that, the most unexpected event happened on 13th November 1872 when a meteorite hit the vessel! It was reported that the shock of impact stunned those on watch whilst balls of fire, like large stars, were seen falling into the water in an extraordinary fireworks display. The crew then had to crush cinders underfoot on the [wooden] deck, accompanied by a strong smell of sulphur! Since 1987, the Sevenstones Lightship has been automated and unmanned, and also acts as an automatic weather station. It is in a very exposed location and is open to most North Atlantic storms.

Lands End peninsula and the Isles of Scilly have almost certainly been Britain’s first landfall for more generations of homecoming mariners than any other part of the British coast. Variously known as the Western Approaches or, to the old seamen, the ‘Chops of the Channel’, this area has more recently been christened ‘The Celtic Sea’ – and maybe this modern title rings truest of all, for it was on the land, bordering these tempestuous waters, that Celts made their last stand against the invaders. Generations of coastal dwellers have laboured on these waters, their origins rooted deeply in the creeks and inlets, and the atmosphere of the long ago still lives on along the granite coastline.

Tourists have been visiting Land’s End for over three hundred years. In 1649, an early visitor was the poet John Taylor, who was hoping to find subscribers for his new book Wanderings to see the Wonders of the West. Later, in 1878, people left Penzance by horse-drawn vehicles from outside the Queens and Union hotels, and travelled via St Buryan and Treen, to see the Logan Rock. There was a short stop to look at Porthcurno and the Eastern Telegraph Company followed by refreshments at the First and Last Inn in Sennen. They then headed for Land’s End, often on foot or horse, because of the uneven and muddy lanes. Today the modern Land’s End has a visitors centre with many attractions but it is still the draw of Land’s End itself, which brings the many visitors every year.